Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh)

The Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh)

The Historical Background

200BC – 2023: A Historically Armenian Region

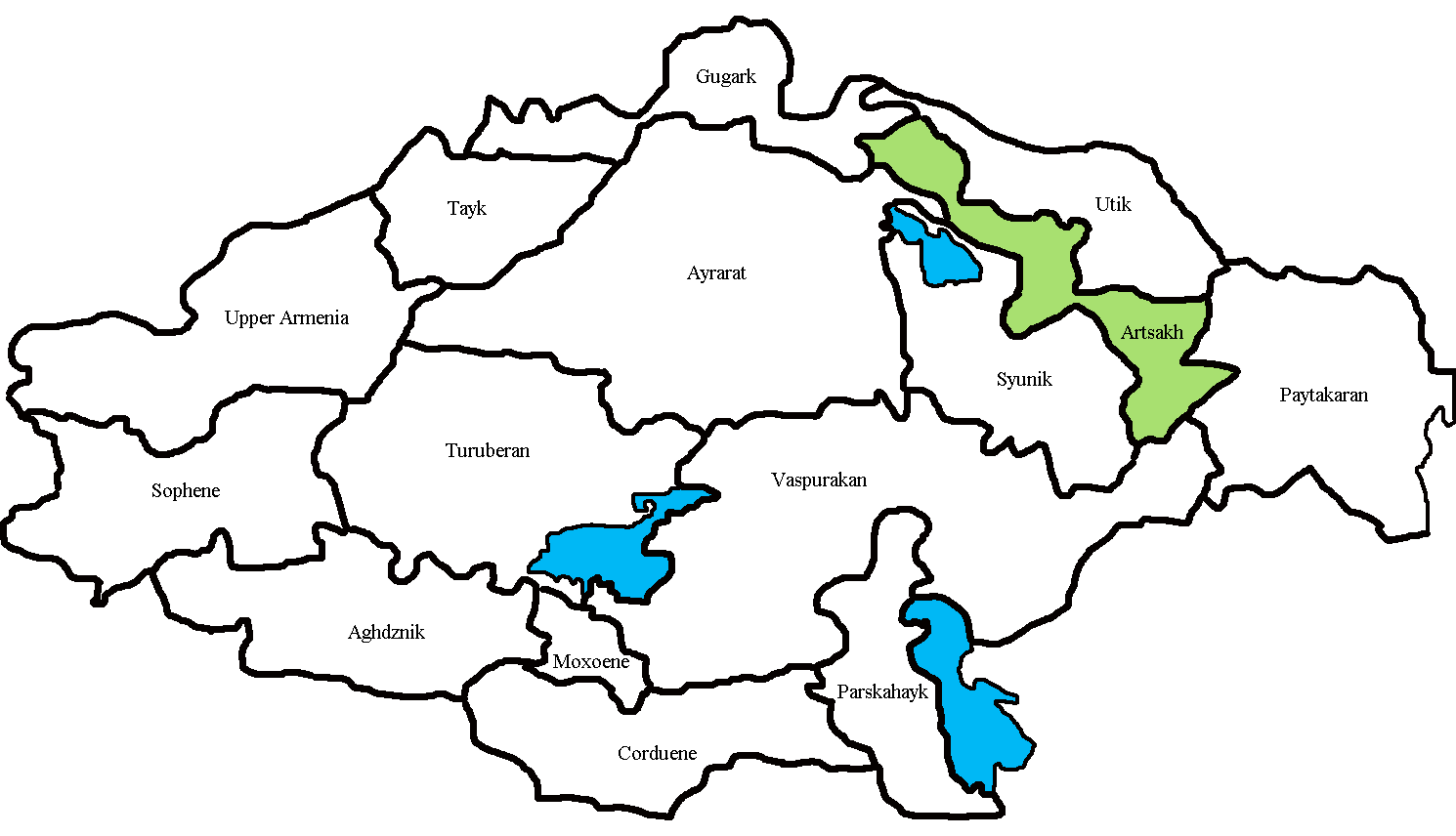

The territory known as Nagorno-Karabakh, referred to by Armenians as Artsakh, was once one of the 15 provinces of the Kingdom of Armenia, existing from around 189 BC to 387 AD.

After a period of foreign rule, in 821AD it formed the Armenian principality of Khachen. Around 1000AD, the region was proclaimed the Kingdom of Artsakh.

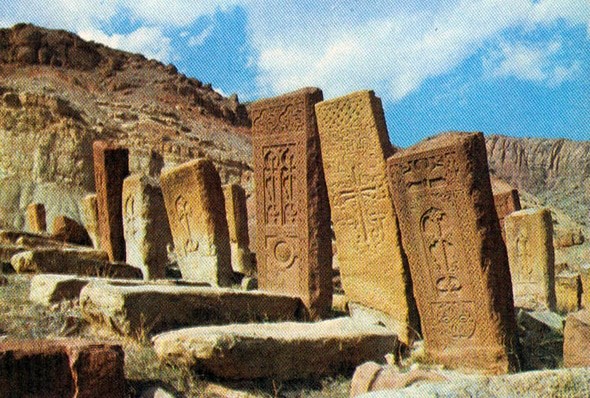

It remained one of the last medieval eastern Armenian territories to maintain its autonomy following the conquest of the Caucasus by Turkic peoples from the 11th century, but it nonetheless remained an overwhelmingly Armenian-inhabited region – a matter reinforced by the huge amount of Armenian cultural heritage which dots the region, including monasteries, cemeteries and Armenian cross-stones (khachkars).

The Artsakh Conflict

The conflict first broke out in 1917 during the formation of the three ethnic republics of Transcaucasia – Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. The population of Artsakh, 95% of which were Armenians at that time, convened its first congress and proclaimed itself as an independent political unit with all required attributes of statehood, including the army and the legitimate authority. The Azerbaijani Democratic Republic launched a military action in response to these peace initiatives of the people of Artsakh. Between 1918-1920, Azerbaijan and Turkish military units carried out massacres against the Armenian population of Artsakh, most notably in the city of Shushi.

The current phase of the conflict began in 1988 when the Azerbaijani authorities began another wave of massacres and ethnic cleansing of the Armenian population across the entire territory of Azerbaijan, resulting in the forced displacement of over 400,000 Armenians living throughout Azerbaijan. Over the years and especially today, Azerbaijan is militarily and diplomatically supported by its key ally Turkey, the successor state to the Ottoman Empire which infamously carried out the Armenian Genocide in 1915.

The First Artsakh War

The First Artsakh War was launched by the Azerbaijani government through a gruesome campaign of ethnic cleansing in 1991 following Artsakh’s declaration of independence through a democratic referendum. The war continued for four years and resulted in over 30,000 deaths.

During the First Artsakh War, Azerbaijan targeted civilians and recruited Islamic extremist mujahideen from Afghanistan and Chechnya to join its army. The Azerbaijani army engaged in numerous human rights violations including wholesale massacres in Sumgait, Baku, Kirovabad and Maraga, and the blockage of humanitarian assistance to besieged populations, notably during the siege of Stepanakert.

Following the military success of Armenian forces in fending off the Azerbaijani attack, a Russian-brokered ceasefire was signed in 1994 between the Artsakh Republic, Armenia, and Azerbaijan in 1994. Though there were occasional, limited efforts by Azerbaijan to reattack the region, twenty-six years of relative peace ensued.

OSCE Minsk Group

The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group sought to encourage a peaceful, negotiated resolution to the conflict. The Group was created in 1992 and consisted of co-chairs Russia, France, and the United States. The OSCE Minsk Group is chiefly responsible for conducting monitoring along the lines of contact and ensuring the implementation of confidence and security building measures. Azerbaijan has however routinely obstructed the activities of the OSCE Minsk Group, preventing monitoring access to ceasefire monitors and refusing to accept the implementation of confidence and security building measures.

The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group sought to encourage a peaceful, negotiated resolution to the conflict. The Group was created in 1992 and consisted of co-chairs Russia, France, and the United States. The OSCE Minsk Group is chiefly responsible for conducting monitoring along the lines of contact and ensuring the implementation of confidence and security building measures. Azerbaijan has however routinely obstructed the activities of the OSCE Minsk Group, preventing monitoring access to ceasefire monitors and refusing to accept the implementation of confidence and security building measures.

The Rise of Ilham Aliyev

In 2003, the President of Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, passed away. His son Ilham Aliyev subsequently power, and has rigged numerous elections and suppressed political opposition to remain in power ever since, on one occasion releasing the results of the election before the polls had opened. On 21 February 2017, by Presidential decree, Aliyev made his wife, Mehriban Aliyeva, Vice-President.

In 2003, the President of Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, passed away. His son Ilham Aliyev subsequently power, and has rigged numerous elections and suppressed political opposition to remain in power ever since, on one occasion releasing the results of the election before the polls had opened. On 21 February 2017, by Presidential decree, Aliyev made his wife, Mehriban Aliyeva, Vice-President.

Armenian hate has flourished under Ilham’s presidency. Ethnic Armenians, regardless of nationality, are banned from entering the country; Schoolchildren are taught to consider all Armenians enemies; Aliyev and his government regularly make and endorse deeply racist statements about Armenians; individuals who kill Armenians abroad, like Ramil Safarov, are rewarded by the state; All of Armenia, including its capital, are incessantly referred to as “Western Azerbaijan”, and various organizations and publications have been created to perpetuate the concept; Armenian heritage in Artsakh and Armenia has been baselessly rebranded by Azerbaijani academics as “Caucasian Albanian”. The UN and a multitude of human rights agencies have documented the dangerous levels of negative Armenian sentiment in Azerbaijan.

This sentiment most notoriously culminated in the complete eradication of all Armenian cultural heritage from the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhichevan. Satellite footage compiled by a team from Cornell University in the USA (access to the region is tightly controlled), over eighty churches have been razed to the ground. The cemetery of Julfa, located close to the Iranian border, contained thousands of intricately carved Armenian khachkars, some over a thousand years old. In 2005, it was set upon by Azerbaijani soldiers with sledgehammers, who smashed them to pieces and dumped the rubble into the nearby Arax River. A priest in neighbouring Iran caught the atrocity on camera, in footage still available online.

A military shooting ground has been built over the cemetery, as Google maps (see below) indicates. A short distance from the cemetery, an Azerbaijani slogan has been carved into the ground, which translates to “Everything for the homeland”. Azerbaijan was never held accountable for this atrocity, no foreign entity has ever been permitted access to it, and the Azerbaijanis maintain that the site never existed.

Nevertheless, Artsakh survived and thrived. In September 2020, it had a population of 150,000 – 160,000 people, predominantly ethnic Armenians. It had three branches of government, including a democratically elected Parliament. It functioned as a democracy with a free economy, and much like Armenia, specialises in wines and spirit production and mining.

Its largest city, Stepanakert, is the capital of the Republic. Other major towns and cities include Martakert, Martuni, and Hadrut. The terrain of Artsakh is extremely mountainous.

The 2020 War and the “ceasefire”

September-November 2020: The Second Artsakh War

On 27 September 2020, the Republic of Azerbaijan, emboldened by strong military support from Turkey, launched an unprovoked and large-scale military invasion of Artsakh. Russia, a member of the OSCE Minsk Group tasked with finding a peaceful resolution to the conflict, and the most significant geopolitical actor in the region, did nothing to stop the hostilities.

Over a period of 44 consecutive days, Azerbaijan relentlessly assaulted Artsakh, resulting in the tragic loss of almost 4000 Armenian lives. Civilian infrastructure, including churches, schools, and hospitals became deliberate targets of Azerbaijan, as confirmed by Human Rights Watch.

Azerbaijan, benefitting from modern weapons systems supplied by military powerhouses Israel and Turkey, and with Turkish military intelligence to hand, took control of significant portions of Artsakh, prompting the displacement of thousands into other areas of the country and into Armenia.

The handful Armenian civilians who remained in areas captured by Azerbaijan were never seen again, with evidence later emerging of their murder. By November 2020, the Azerbaijani army were within sight of Stepanakert, the capital of the region.

November 2020: The “Ceasefire” Agreement

On 9 November 2020, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia signed a ceasefire agreement known as a “Trilateral Statement”. Pursuant to Article 3 of the ceasefire agreement, peacekeeping forces from Russia were to remain deployed in the region until 2025, with the possibility of an extension thereafter. Under Article 6 of the agreement, a narrow corridor, known as the Lachin Corridor, would provide the inhabitants of Artsakh with a connection to Armenia. This connection was to remain under the control of the Russian peacekeeping forces. Azerbaijan also agreed to “guarantee the security of persons, vehicles and cargo moving along the Lachin Corridor in both directions”.

However, Azerbaijan repeatedly breached the ceasefire – and on almost every occasion committed grave violations of international law, including torture, murder, and desecration of corpses. Many of these atrocities were filmed and subsequently posted on social media, presumably to instil fear and distress amongst Armenians. Farmers and schools shot at, civilian vehicles pushed off the road – Most have been digitally archived, and among these atrocities the execution of Armenian soldiers at Lake Sev in October 2022 and the rape, murder and mutilation of female soldier Anoush Apetyan in September 2022 are worth specific mention.

September 2022: The Azerbaijani Invasion of Armenia

On 12 September 2022, Azerbaijan launched an invasion into the Republic of Armenia. The towns of Vardenis, Goris, Sotk, Jermuk, and other cities were struck with artillery, drones, and heavy weapons. Though the aggression did not last more than a few days, 7600 Armenian civilians were displaced, 140 square kilometres of Armenian territory were subsequently occupied, and 200 Armenian servicemen were killed.

The attack prompted then Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, to visit Armenia and express her support for the country, its sovereignty and security. Delegations from the EU attended Armenia to inspect the damage inflicted by Azerbaijan and the occupation of Armenian territory. It was following this event that the EU’s increased involvement in the conflict began, most notably via their border Monitoring Mission.

Notably, the CSTO, the Russian-led security bloc of which Armenia was a member, did nothing to halt hostilities nor did it provide any support to Armenia.

The Artsakh Blockade

12 December 2022 – September 2023

On 12 December 2022, individuals of Azerbaijani origin, consisting of both civilians and soldiers dressed in civilian attire, masqueraded as “eco-activists” and established tent encampments, effectively closing off the Lachin Corridor. This corridor served as the lifeline connecting Artsakh to Armenia.

The idea that protesters were able to access an area fiercely guarded by Azerbaijani and Russian forces, with the equipment necessary to stage a prolonged protest was laughable – even more so when one considers how intensely Azerbaijan suppresses all voices of dissent. It is almost certain that these individuals, some of whom were later identified as belonging to members of the Azerbaijani military and fascist groups like the Grey Wolves, were installed by the Azerbaijani government.

Nevertheless, the Russian peacekeeping forces did nothing to intervene, and on some occasions were seen socialising with the protesters.

This initial stage marked the beginning of a blockade that persisted for the following 9 months, severely restricting the freedom of movement of goods and all remaining 120,000 Armenians living in Artsakh. During this time, the gas supply to the region was periodically disrupted, almost certainly by Azerbaijan, who controlled territories through which the pipelines ran. One such disruption was acknowledged by British Minister Leo Docherty in January 2023. The gas was stopped during winter in a deliberate attempt to make life for the Armenians living in a mountainous region as difficult as possible. Such obstructions had already been recorded in 2022.

Not only did the blockade prevent the transport of people, but they also repeatedly blocked members of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the delivery of food and medication, and caused water, electricity, and internet access to be heavily rationed.

In a provisional measure dated 22 February 2023, the International Court of Justice, which was already hearing a case commenced by the Armenia against Azerbaijan concerning the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, issued a provisional measure requiring Azerbaijan to “ensure unimpeded movement of persons, vehicles, and cargo along the Lachin Corridor”.

Azerbaijan ignored the order, and on 28 April 2023, once the Azerbaijani government had established an illegal checkpoint on the corridor, the “eco-protesters” left their posts and were replaced by Azerbaijani soldiers. Again, the Russian peacekeeping forces did nothing to intervene. The EU monitoring mission continued to observe the point at which the Lachin Corridor met Armenia (see below), having been denied access to the region or Azerbaijan.

In August 2023, these EU monitors came under fire by Azerbaijani troops during their monitoring activities along the Armenia-Azerbaijan border.

In a United Nations Security Council meeting on 16 August 2023, the majority of participating countries either directly attributed the blockade to Azerbaijan or otherwise called for the corridor be opened. However, Azerbaijan maintained the blockade.

The Final Offensive and Ethnic Cleansing of September 2023

19 September 2023: Azerbaijan Launches a Full-Scale Offensive

In September 2023, at the height of the escalating humanitarian and economic crisis, images began to appear on social media of ranks of Azerbaijani military vehicles bearing an upside-down A symbol, not unlike the Russian “Z” seen on vehicles shortly before the latter’s invasion of Ukraine. Armenians took these images to mean that another military escalation was imminent, and they were sadly proven right.

On 19 September 2023 Azerbaijan launched a large-scale military offensive on Artsakh. The military offensive targeted civilians and civilian-dense areas, including the capital Stepanakert, Martuni, Askeran, Martakert, and Taghard. Tens of thousands of civilians were initially barred from evacuation to neighbouring Armenia since access via the only humanitarian corridor was still blocked at Lachin.

Azeri-controlled social media networks and troll farms circulated videos showing the torture and mutilation of Armenians at the hands of Azerbaijani soldiers. Information gathered from social media, though unverified evidence indicates that during this time rapes, beheadings, and executions of both adults and children were committed.

According to testimony gathered from refugees, internet connection was intermittently cut by Azerbaijan during the conflict. Given they had already taken control of the Lachin Corridor connecting Artsakh to the outside world, Azerbaijan forbade access to the region by media, NGOs, civil society groups, or UN special rapporteurs, preventing any independent verification of what was happening within.

20 September 2023: The Ethnic Cleansing of Artsakh

With the psychological trauma of the war and blockade, their starvation conditions, under shelling and bombardment of the Azerbaijani military, and conscious of the cruelty Azerbaijanis were more than capable of indiscriminately inflicting, hardly any of the Armenian inhabitants of Artsakh felt safe staying.

It was only when it became apparent to Azerbaijan that civilians were fleeing en masse that they allowed the Lachin Corridor to open, knowing full well that such a move would achieve the ethnic cleansing of Artsakh.

Within minutes of the opening of the Corridor, people frantically grabbed the bare minimum of belongings, such as passports, legal documents, and a few items of clothing, and on foot, using cars, trucks, carriages, and tractors, travelled towards Armenia. There are reports of people walking for miles, children as young as 11 driving cars, and civilians being struck by gunfire and shrapnel by Azerbaijanis as they fled.

A trip that would normally last no more than two hours took over thirty-eight hours as Armenians jammed the only way out. The displacement lasted eight days, during which time practically the entire Armenian population of Artsakh fled to Armenia, leaving behind their homes, personal belongings, churches, centuries-old cemeteries, museums, schools, everything which defined them as the indigenous inhabitants of the region.

In an attempt to end the Azerbaijani military onslaught, the terms of a new ceasefire were established. According to these new terms, the Artsakh Defence Army was to be immediately disbanded, laying down their arms and leaving combat positions. The Artsakh Republic was to be unconditionally surrendered and integrated into Azerbaijan. All weapons and heavy equipment were to be surrendered, in a process overseen by the Azerbaijani government. There is some unverified evidence to suggest that at least some of the weapons have since been transferred to Russia, presumably for use in the war in Ukraine.

A United Nations Mission to the region in October 2023 confirmed that over 100,000 Armenians, practically the entire population of the region remaining after the 2020 war, had fled.

Condition of Refugees Upon Arrival In Armenia

Preliminary medical assistance given and reports taken from refugees arriving in the border areas of Armenia indicated that the Artsakh Armenians had been subjected to tremendous physical and/or psychological violence. 18 instances of murder, including the murder of children, indiscriminate use of missiles, and hundreds of cases of civilians injured by shrapnel.

Arbitrary Detention of Armenians during the Ethnic Cleansing

As the population of Artsakh fled, the Azerbaijani military detained specific individuals, despite the Azerbaijani government having formerly made assurances of amnesty. These include former Artsakh presidents Arkady Ghukasyan, Bako Sahakyan, and Arayik Harutyunyan. Other political POWs include Ruben Vardanyan, Davit Ishkhanyan, Davit Babayan, Davit Manukyan, and Levon Mnatsakanyan. They remain incarcerated.

Sample of Initial Responses from the International Community

On 27 September 2023, the French Foreign Ministry issued a statement in which it committed itself to “supporting Armenia and the Armenian people, as well as the refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh who were forced to flee their land and their homes in their tens of thousands following the Azerbaijani military offensive and nine months of an illegal blockade.”

On 27 September 2023, the French Foreign Ministry issued a statement in which it committed itself to “supporting Armenia and the Armenian people, as well as the refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh who were forced to flee their land and their homes in their tens of thousands following the Azerbaijani military offensive and nine months of an illegal blockade.”

On 5 October 2023, following a debate in the EU Parliament, MEP’s issued a statement describing the Armenian’s fleeing from Nagorno-Karabakh as ethnic cleansing. They strongly condemned Azerbaijan’s pre-planned and unjustified military attack against Nagorno-Karabakh, called for the adoption of targeted sanctions against Azerbaijani government officials responsible for ceasefire violations and human rights abuses, and demanded that the EU suspend any negotiations on a renewed partnership and current energy memorandum of understanding with Azerbaijan.

On 5 October 2023, following a debate in the EU Parliament, MEP’s issued a statement describing the Armenian’s fleeing from Nagorno-Karabakh as ethnic cleansing. They strongly condemned Azerbaijan’s pre-planned and unjustified military attack against Nagorno-Karabakh, called for the adoption of targeted sanctions against Azerbaijani government officials responsible for ceasefire violations and human rights abuses, and demanded that the EU suspend any negotiations on a renewed partnership and current energy memorandum of understanding with Azerbaijan.

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

On 10 October 2023, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution strongly condemning the military operation launched by the Azerbaijani army in Nagorno-Karabakh on September 19, describing it as Azerbaijan’s “clear disregard” for international norms. It also warned Azerbaijan that “the practice of ethnic cleansing, may give rise to individual criminal responsibility under international law.”

On 10 October 2023, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution strongly condemning the military operation launched by the Azerbaijani army in Nagorno-Karabakh on September 19, describing it as Azerbaijan’s “clear disregard” for international norms. It also warned Azerbaijan that “the practice of ethnic cleansing, may give rise to individual criminal responsibility under international law.”

US Mission to International Organizations

On 11 October 2023, The US Mission to International Organizations issued a statement, in which it explained “this massive displacement of ethnic Armenians from their homes stems from Azerbaijan’s military operation launched on September 19th and a nine-month long blockage of the Lachin corridor leading to dire humanitarian conditions.”

On 11 October 2023, The US Mission to International Organizations issued a statement, in which it explained “this massive displacement of ethnic Armenians from their homes stems from Azerbaijan’s military operation launched on September 19th and a nine-month long blockage of the Lachin corridor leading to dire humanitarian conditions.”

UK Foreign Office

The UK FCDO issued a statement on 5 October 2023. In sharp contrast to its American and European contemporaries, the UK did not attribute any responsibility to Azerbaijan, instead urging “both Armenia and Azerbaijan to continue negotiations and to do all they can to reduce tensions and avoid further escalation, including through Azerbaijan making clear its respect for Armenia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and for the rights and security of the remaining ethnic Armenian community in Nagorno-Karabakh.”

The UK FCDO issued a statement on 5 October 2023. In sharp contrast to its American and European contemporaries, the UK did not attribute any responsibility to Azerbaijan, instead urging “both Armenia and Azerbaijan to continue negotiations and to do all they can to reduce tensions and avoid further escalation, including through Azerbaijan making clear its respect for Armenia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and for the rights and security of the remaining ethnic Armenian community in Nagorno-Karabakh.”

International Court of Justice

On 17 November 2023, in the ongoing case concerning the Application of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Armenia v Azerbaijan), the ICJ issued an Order requiring Azerbaijan to:

On 17 November 2023, in the ongoing case concerning the Application of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Armenia v Azerbaijan), the ICJ issued an Order requiring Azerbaijan to:

“(i) ensure that persons who have left Nagorno-Karabakh after 19 September 2023 and

who wish to return to Nagorno-Karabakh are able to do so in a safe, unimpeded and

expeditious manner;

(ii) ensure that persons who remained in Nagorno-Karabakh after 19 September 2023 and

who wish to depart are able to do so in a safe, unimpeded and expeditious manner; and

(iii) ensure that persons who remained in Nagorno-Karabakh after 19 September 2023 or

returned to Nagorno‑Karabakh and who wish to stay are free from the use of force or

intimidation that may cause them to flee”.

Azerbaijan is also expected to uphold the protection and preservation of identity, registration, and private property documents in administrative and legislative practices.

The Current Situation

Status of Refugees

Numerous foreign states have pledged funds to Armenia to help it support the influx of refugees (adding 3% to Armenia’s entire population), but the task has nevertheless been tremendously difficult. As of March 2024, no Artsakh Armenians have been allowed by Azerbaijan to return to their homes, nor have any measures been proposed by Azerbaijan to facilitate such a process.

On the contrary, Azerbaijan continues to act in ways which would quite easily be interpreted as ensuring no Armenian can ever return to the region. In October 2023, Azerbaijan renamed one of the streets in the city of Stepanakert after Enver Pasha, one of the architects of the Armenian Genocide. In the same month, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev was filmed wiping his feet on the Artsakh flag in Stepanakert. In March 2024, footage was aired on Azerbaijan television of various buildings and monuments in Stepanakert, including its Parliament building, being demolished.

Cultural Heritage

Throughout Azerbaijan’s assault on Artsakh, Armenian cultural heritage has been defaced, altered or destroyed. Given Azerbaijan’s appalling record of destruction of Armenian cultural heritage in Nakhichevan, there are genuine concerns that the cultural heritage of Artsakh, comprised of more than four thousand historical and cultural monuments, are under the threat of total destruction. Among them are churches, khachkars, burial grounds, historical cemeteries, bridges. There are already alarming signals, with at least one instance of destruction, the razing of the Zoravor Surb Astvatsatsin church near the town of Mekhakavan, confirmed by the BBC.

The conical roof of the Armenian Ghazanchetots Cathedral in Shushi, one of the most iconic pieces of Armenian cultural heritage in the region, was been removed by Azerbaijani authorities, depriving it of its typically Armenian appearance – no work has been carried out to the building since, and Azerbaijani outlets are currently referring to the building as “Russian Orthodox”. The Armenian Church of Holy Resurrection in Hadrut has been vandalised, and its cross removed. The Cross atop the 7th century Vankasar church was recently removed, as made clear in an Azerbaijani tourism social media post. Proposals have also been made by Azerbaijan to turn another Armenian church, this time in Berdzor, into a mosque, and previously Azerbaijan has expressed a desire to remove Armenian inscriptions from various other heritage sites, in a move condemned by both the US Commission on International Religious Freedom and EU Parliament. There are other instances of vandalism and destruction, too many to exhaustively list here. To date, Azerbaijan has yet to invite UNESCO to the region to document cultural heritage, both Armenian and Azerbaijani, despite pleading with the organisation to visit for many years prior to the 2020 War.

The conical roof of the Armenian Ghazanchetots Cathedral in Shushi, one of the most iconic pieces of Armenian cultural heritage in the region, was been removed by Azerbaijani authorities, depriving it of its typically Armenian appearance – no work has been carried out to the building since, and Azerbaijani outlets are currently referring to the building as “Russian Orthodox”. The Armenian Church of Holy Resurrection in Hadrut has been vandalised, and its cross removed. The Cross atop the 7th century Vankasar church was recently removed, as made clear in an Azerbaijani tourism social media post. Proposals have also been made by Azerbaijan to turn another Armenian church, this time in Berdzor, into a mosque, and previously Azerbaijan has expressed a desire to remove Armenian inscriptions from various other heritage sites, in a move condemned by both the US Commission on International Religious Freedom and EU Parliament. There are other instances of vandalism and destruction, too many to exhaustively list here. To date, Azerbaijan has yet to invite UNESCO to the region to document cultural heritage, both Armenian and Azerbaijani, despite pleading with the organisation to visit for many years prior to the 2020 War.

Armenian POWs and Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

As per the terms of the 2020 ceasefire, both parties were required to release all prisoners of war. However, at least six Armenians captured during the 2020 war remain in detention in Azerbaijan (though it is believed that the number being detained is higher).

In July 2023, 68-year-old Artsakh resident Vagif Khachatryan was being transported from Artsakh to Armenia to receive medical treatment. En route, he was seized by Azerbaijani soldiers, transferred to the Azerbaijani capital of Baku, and after a sham trial, was sentenced to 15 years in prison, the maximum sentence possible for someone of his age. His seizure prompted the halting of all medical evacuations from Artsakh. He remains imprisoned in Azerbaijan.

The UK’s Role Today

The conduct of the Azerbaijani government and its military has made it impossible for the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh – having lived in that region since time immemorial – to remain there or return without iron-clad international guarantees. There is little doubt that the end goal for Azerbaijan was to eliminate the Armenian presence from the region, as part of a wider plan to entirely remove Armenians from the Caucasus, in much the same way as Turkey did in Asia Minor in 1915.

ANC UK will accordingly continue to lobby the British government to:

- Pledge greater aid to the forcibly displaced population of Artsakh;

- Acknowledge that Azerbaijan’s military offensive in Artsakh, viewed through the lens of the blockade and violations of humanitarian law, constituted ethnic cleansing;

- Apply targeted sanctions against members of the Azerbaijani regime responsible for the ethnic cleansing.

- Publicly support the right of return of the population of Artsakh to their homeland pursuant to the terms of the ICJ interim measure, Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Right 1948, Article 12 of The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194 (III);

- Publicly support the facilitation of that return with the instalment of multinational or UN peacekeeping force to ensure atrocities cannot be committed against the Armenian people again, along with self-governing rights bestowed to the local population;

- More vigorously lobby for the protection of the cultural and religious heritage of Armenians by international organisations such as UNESCO;

- Curtail Azerbaijan from further claims on the sovereign territory of Armenia and insist on their withdrawal from Armenian territory occupied from 2020 to present.

[/vc_column][/vc_row]