Armenian Genocide

What Happened?

Map of deportation routes and massacres of the Armenian Genocide,

in R. Hewsen, ‘Armenia: A Historical Atlas’, 1st ed (2001), University of Chicago Press, p.23

The Armenian Genocide was a campaign of extermination carried out by the Ottoman Empire against its Christian Armenian population, most of whom lived in what is now the eastern half of Turkey. It began in the late 19th century, and continued until the emergence of the Republic of Turkey in 1923.

In late 1913, the Ottoman government formed the “Special Organisation”, a paramilitary force consisting of Circassians and Kurds, as well as more than 10,000 convicted criminals, including rapists and murderers, who were offered a chance to redeem themselves by assisting the state in annihilating the Armenians.

The worst period of the genocide began on 24 April 1915, during the First World War, when the Ottoman Turkish government, riding a wave of ethnonationalist sentiment, rounded up hundreds of members of the Armenian intelligentsia in what is now Istanbul, loaded them onto trains, and transferred them to various holding centres across the region, where most were executed.

The Ottoman Parliament then passed the Tehcir Law on 27 May 1915, authorising the deportation of any individuals perceived as a threat to national security, which in practice included the approximately two million Armenians who called the region home.

In September 1915, the “Temporary Law of Expropriation and Confiscation” was passed, empowering the state to confiscate the personal property of Armenians, including land, buildings, and bank accounts, businesses, and also community property, such as churches.

In reality however, both of these measures were implemented to legitimise mass murder, the destruction of swathes of Armenian heritage, and the theft of Armenian land and property, today worth billions of pounds.

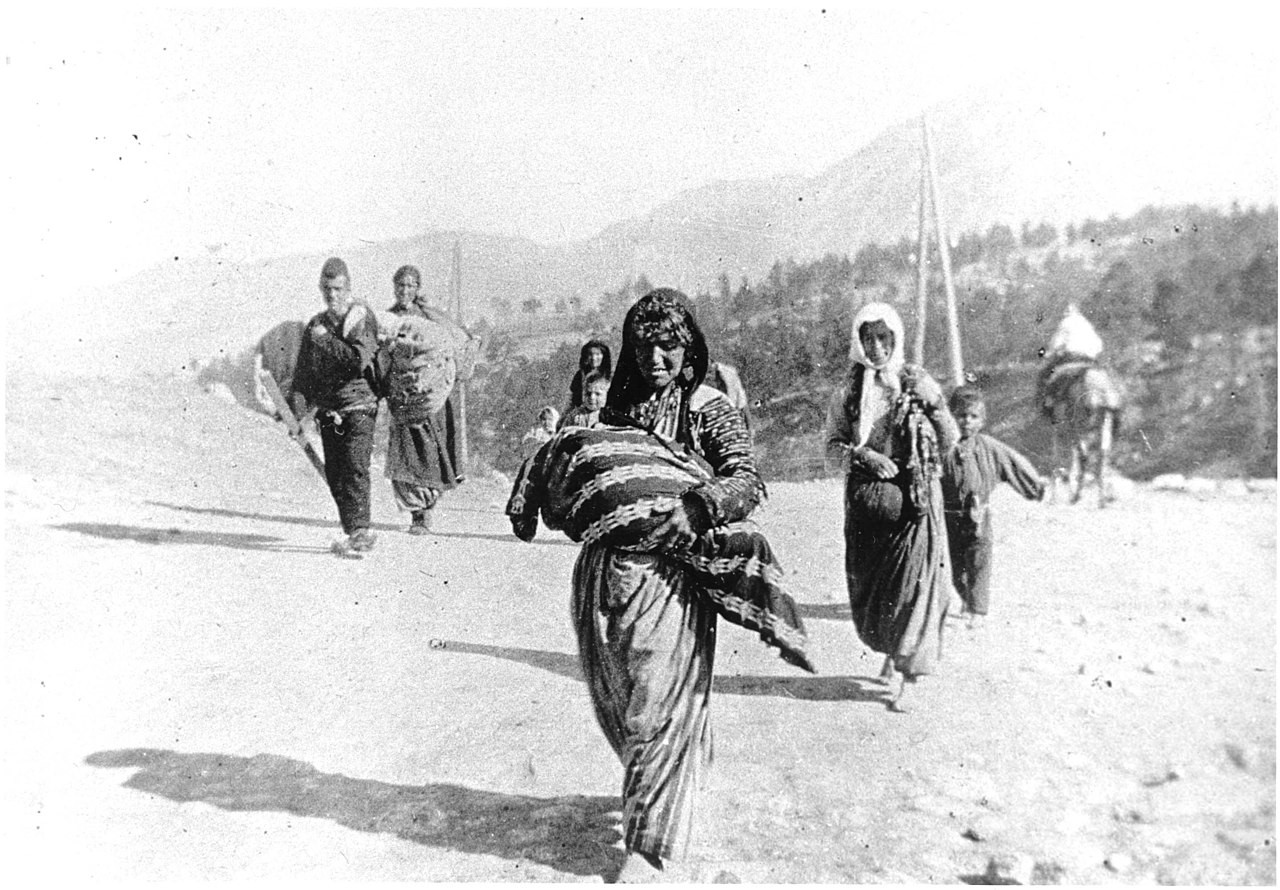

“Those who fell by the wayside” – a photograph of bodies included in the memoirs of

Henry Morgenthau Snr, U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1916:

see H. Morgenthau, ‘Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story’, 1st ed (1918), Doubleday, p 314.

On the government’s endorsement, Armenian towns, villages and monastic complexes across the region were raided by Ottoman and Kurdish soldiers, their inhabitants killed, their properties seized, valuables plundered, and treasured cultural and religious buildings, some dating back to the 11th century, were desecrated or demolished.

Survivors, mostly women, children and the elderly, were forced to march south into the Syrian desert, with either minimal or no food and water, and along the way faced regular physical and sexual violence. Young women were forced into sexual slavery or made to marry Ottoman soldiers under threat of death. Many children who were orphaned were Islamized and adopted by Turkish or Kurdish families.

By 1917, approximately 1.5 million Armenians had been killed. Many distinguished witnesses of all nationalities attested to and documented the scale, barbarity, and premeditated, systematic nature of the bloodshed with letters, news reports and photographs. Hundreds of thousands of Armenians fled the region, creating large diasporas in America, France, and Russia to name but a few.

Courts martial took place in Istanbul in 1919 to bring those who had participated in genocide to justice, described at the time as “Armenian massacres”. However, the three heads of the Ottoman government who ultimately orchestrated the genocide had since fled the region, and were sentenced to death in absentia. Those sentences were never formally passed.

Effort was also made by the international community to hold trials in Malta in a manner similar to the trial of Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg, but as international law was in its infancy at the time, establishing a framework in which to do so was difficult. In any event, following Turkish victory against Britain, France and Greece in the Turkish War of Independence in 1923, the newly formed Republic of Turkey was granted wholesale immunity from prosecution for crimes committed between 1914 and 1922 in the Treaty of Lausanne.

Today, only around 70,000 known Armenians live in Turkey, i.e. around three percent of the region’s pre-1915 population. Most Armenian cultural heritage in the country has been destroyed.

The Current Situation

Since 1948, the Genocide Convention has provided the world with a foundational definition of genocide. It defined as:

“Any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

The overwhelming academic consensus is that the atrocities committed against Armenians satisfy this definition, and constituted genocide. There is to date no credible counterargument to this position. Most notably, Raphael Lemkin, who invented the term ‘genocide’ in 1944 and campaigned for the creation of the Genocide Convention, has been recorded numerous times referring to the events as a genocide; a report produced by the UN Sub-Commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities in 1985 points to the Armenian genocide as a historic example of genocide; and in 1997, the International Association of Genocide Scholars unanimously passed a resolution recognising the Ottoman massacres of Armenians as genocide.

The following countries and international political bodies spanning multiple geopolitical faultlines have also formally recognised the treatment of Armenians during this period as genocide:

In addition, dozens of regional governments around the world, from Michoacán in Mexico, to Ukrainian Crimea, to New South Wales in Australia, have formally recognised the genocide.

Despite the enormous body of evidence and expert opinion weighing against them, successive Turkish governments have denied that a genocide took place, maintaining that the Armenians were merely resettled elsewhere.

More radical elements of Turkish society and its government go one step further and endorse the offensive and entirely discredited narrative that the destruction of the Armenian population was a justifiable course of action, that Armenians have fabricated or exaggerated their claims of genocide, and/or in extreme cases, that it was the Armenians themselves who committed genocide against the Turks.

The UK’s Initial Response to the Armenian Genocide

At the time of the genocide, the British government had been one of the most vocal members of the international community condemning the appalling treatment of Armenians, documenting their suffering, and spearheading efforts to bring the perpetrators to justice. It is right that the United Kingdom should revive its historic support for Armenians and recognise the Armenian Genocide today.

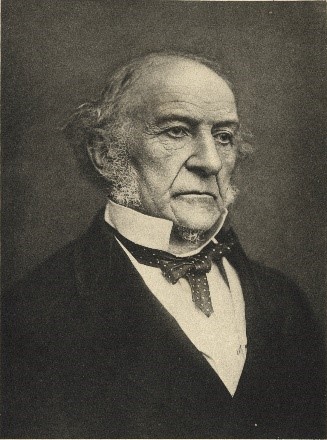

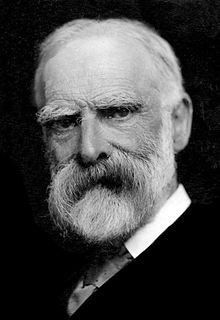

In 1894, when Ottoman Empire began massacring Armenians across the region in an event now known as the Hamidian Massacres, photographs and accounts of the atrocities were presented to a shocked British public. In response, former Prime Minister William Gladstone and incumbent Prime Minister Lord Salisbury both called for international intervention. In a speech in 1895, the former famously stated “To serve Armenia is to serve civilization”. A charitable campaign run by The Times also raised £55,000, equivalent to £5.6 million in 2022, to provide food, clothing, and shelter to persecuted Armenians.

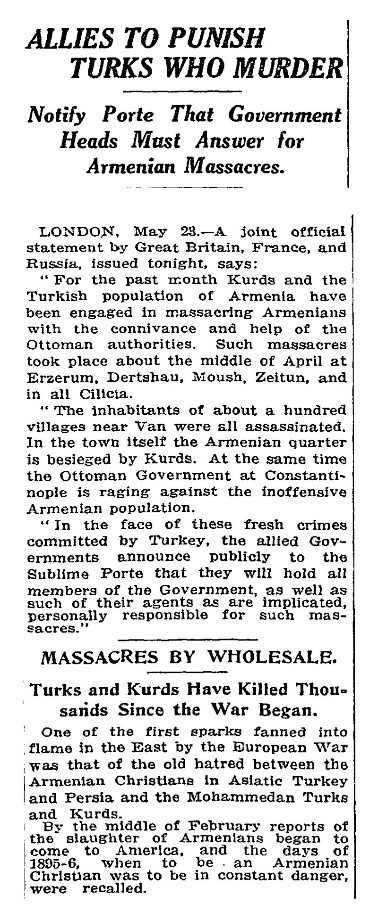

In May 1915, and in light of mounting evidence of a concerted effort to destroy the Armenians, the governments of the United Kingdom, France and Russia issued a joint declaration describing the atrocities as “crimes against humanity and civilization” and vowed to “hold personally responsible [for] these crimes all members of the Ottoman government and those of their agents who are implicated in such massacres”. The declaration was printed in newspapers around the world.

In 1916, the British government commissioned a Parliamentary Blue book to document the genocide as it took place, entitled ‘The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire’. Compiled by Arnold J. Toynbee and Viscount Bryce and published in October 1916, the 742-page book, still available today, contained verified statements from eyewitnesses of the Armenian as well as the Assyrian genocides in the Ottoman Empire. The book also contained second-hand reports, letters, dispatches, and news articles proving that the Ottoman Empire was intentionally targeting and destroying its Armenian population, totalling 149 documents and 15 appendixes.

Toynbee wrote at p. 649 that “in one way or another, the Central Government enforced and controlled the execution of the scheme, as it alone had originated the conception of it; and the Young Turkish Ministers and their associates at Constantinople are directly and personally responsible, from beginning to end, for the gigantic crime that devastated the Near East in 1915”.

The contents of the book were subsequently verified by scholars, including former American Bar Association President Moorfield Storey (1845-1929), MP and Vice-Chancellor of Sheffield University H.A.L. Fisher (1865-1940), and Oxford professor Gilbert Murray (1866-1957). Murray stated that “… the evidence of these letters and reports will bear any scrutiny and overpower any scepticism. Their genuineness is established beyond question.”

In 1929, Winston Churchill, who commanded British forces against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, described the actions of the Ottomans at p. 98 of his book, ‘The World Crisis’, as “massacring uncounted thousands of helpless Armenians, men, women, and children together, whole districts blotted out in one administrative holocaust – these were beyond human redress”.

In 1929, Winston Churchill, who commanded British forces against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, described the actions of the Ottomans at p. 98 of his book, ‘The World Crisis’, as “massacring uncounted thousands of helpless Armenians, men, women, and children together, whole districts blotted out in one administrative holocaust – these were beyond human redress”.

He continued, at p. 405: “In 1915 the Turkish government began and ruthlessly carried out the infamous general massacre and deportation of Armenians in Asia Minor…the clearance of the race from Asia Minor was about as complete as such an act, on a scale so great, could well be. There is no reasonable doubt that this crime was planned and executed for political reasons.”

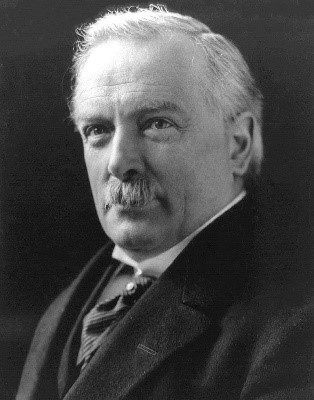

David Lloyd George also referred to the genocide as a “holocaust” at p. 811 of his 1939 memoirs. Lloyd George, who had been British Prime Minister between 1916 and 1922, went on to say “by these atrocities, almost unparalleled in the black record of Turkish misrule, the Armenian population was reduced in numbers by well over a million”. It is clear from subsequent passages in his memoirs that George regretted the lack of a more robust response to the atrocities by the British.

David Lloyd George also referred to the genocide as a “holocaust” at p. 811 of his 1939 memoirs. Lloyd George, who had been British Prime Minister between 1916 and 1922, went on to say “by these atrocities, almost unparalleled in the black record of Turkish misrule, the Armenian population was reduced in numbers by well over a million”. It is clear from subsequent passages in his memoirs that George regretted the lack of a more robust response to the atrocities by the British.

The Case for Recognition

1. It is immoral and oppressive to subject matters of historical fact to the whims of political convenience. The Armenian Genocide, like the Holocaust or slavery, is a well-documented event in human history, and in light of overwhelming evidence of an intentional, concerted effort to destroy the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire, no label other than genocide, the word invented to describe that precise act, is sufficient.

2. A crime unpunished is a crime encouraged. Without effective political (and wherever possible, legal) accountability for acts of genocide, potential perpetrators of genocide are emboldened by a sense of impunity. A key example of this came in August 1939, when Adolf Hitler used the Armenian Genocide to justify the barbaric nature of his plan to invade Poland. Giving a speech to senior members of the German army at his country retreat in Berchtesgaden, he said “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?” (a transcript of his speech can still be found in British Foreign Office archives).

3. Millions of Armenians today are the descendants of genocide survivors, and have inherited the trauma of events which, by virtue of Turkey’s persistent denial, has not been laid to rest. To make matters worse, Turkey, as well as the Republic of Azerbaijan, go to great lengths to spread the thoroughly discredited narrative that Armenians fabricated the genocide, or provoked the Ottomans into destroying them. Greater recognition of the genocide, including recognition by the United Kingdom, will help put a stop to Turkey and Azerbaijan’s morally repugnant propaganda efforts, chiefly by raising public awareness and helping advance further study of the genocide.

4. Turkey’s outright denial of the genocide has contributed to the total lack of diplomatic relations between Armenia and Turkey. Global political acknowledgment that the events constituted genocide (global academic acknowledgment has long been established) will exert pressure on the Republic of Turkey to accept the nature of its past, thus opening an era of reconciliation between Turkey and Armenia.

5. Recognition of the Armenian Genocide will reinforce the United Kingdom’s commitment to the 1948 Genocide Convention, to which the UK acceded in 1970, strengthening our country’s global prestige for standing up for human rights and justice.

6. The Armenian Genocide drew shock and condemnation from the international community at the time, just as the modern world has been shocked by the genocidal treatment of Uighurs in China, the Yazidis by Islamic State, the Rohingyas in Myanmar, and the Darfurians in Sudan. We need to ensure that all historic crimes against ethnic, religious, and national groups are reported and recognised for what they are, so they can be cited and used as precedents when genocide rears its ugly head once more.

The British Government’s Current Position

The UK is now among the last leading countries in the west and one of just two G7 member states who has not recognised the atrocities committed against the Armenians as genocide.

The British government’s current position on attribution of the term is that “determinations of genocide should be made by competent courts, rather than by governments or non-judicial bodies, such as parliament”.

Flaws and Inconsistencies in That Position

1. There is no law requiring the government to only recognise instances of genocide as those determined by a court. There is no domestic statute, domestic or international court decision, bilateral or multilateral treaty, or UN resolution requiring the United Kingdom, or indeed the government of any country, to maintain such a policy.

2. The policy has created a confusing situation in which the British Parliament can (and has) passed motions declaring certain atrocities as genocide, but the government will not. Since adopting this approach, Parliament has recognised the Ukrainian Holodomor and the Chinese treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang as genocide, but the government has not. This implies that the government respects the determination of courts, even those of a foreign jurisdiction, more than its own Parliament.

3. Clinging to the need for a judicial decision is an inflexible policy depriving the government of any autonomy on the subject. If, no matter how much evidence began to mount, a court case in a textbook case of genocide never took place, the government would be trapped, forever incapable of recognising the atrocity by its rightful name, no matter how much evidence comes to light and no matter how much the academic or legal perspective changes.

4. It fails to recognise the grim realities of genocide, in that they often take place with impunity. The government cannot simply trust that a court decision can or will always be made in the right cases – after all, the United Kingdom was in 1923 one of the signatories to a Treaty which expressly prohibited the prosecution of Turkish nationals for their role in the Armenian Genocide.

5. The preamble of the 1948 Convention binds the United Kingdom into recognising that “at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity”. Therefore, by maintaining its policy, the British government is contradicting the Convention in both spirit and wording.

Addressing Broader Challenges to Genocide Recognition

There must be indisputable evidence of a specific decision to exterminate the Armenians

1. There is no requirement for evidence of a specific, express decision to eliminate an ethnic group in order for the term ‘genocide’ to apply. When the Nazis planned and implemented the Holocaust, they did not specify that they intended on exterminating the various groups they targeted, most prominently the Jews. Infamously, in respect of the Jews they used codewords for their crimes – for example, the “Final Solution”, “transferred”, and “resettlement”.

2. Since the Holocaust, international legal jurisprudence has developed to appreciate that genocides can take place without evidence of an express command or specific order to commit genocide. In the case of Jean-Paul Akayesu, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda held that it was possible to infer genocidal intent from the scale of atrocities committed, their general nature, in a region or a country, or the fact that there had been a deliberate and systematic targeting of victims on account of their membership of a particular group, while excluding the members of other groups. This principle was developed further in July 2001 by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in the case of Goran Jelisić and reiterated in the 2013 case of Radovan Karadžić. Inferred intent is accordingly an established principle of international criminal law.

3. With the above in mind, there is more than ample evidence from which one can infer that Ottoman Empire, under the codeword of “deportation”, intended to destroy its ethnic Armenian population.

Genocide recognition is something confined to academic circles or courts

4. Academics establish facts by analysing evidence, but generally do not cast personal judgment upon those facts. In a democratic state, governments reflect and represent the moral conscience of their country, and, in light of conclusions drawn by academics, should express the morality of their constituents. It is accordingly the responsibility of all three branches of the government to recognise genocide wherever it had objectively occurred.

Genocide recognition would harm relations with the Republic of Turkey

5. Claims that recognition of the genocide would damage economic relations with Turkey are completely unfounded. Bilateral trade between Turkey and almost all genocide-recognising countries has increased since their recognition, in some cases growing tenfold. Beyond empty threats from Turkish government figures immediately following instances of recognition, history demonstrates that recognition itself has little to no bearing on the political/diplomatic relationship between the recognising state and Turkey thereafter.

Notable Figures who Recognise the Armenian Genocide

Below is a list of influential British and foreign figures who recognise the Armenian Genocide.

Lord Alton of Liverpool

Lord Alton of Liverpool

“The U.K.’s dismal, cynical failure to recognise and name the atrocity crimes committed against the Armenians as a Genocide encourages today’s genocidaires to believe that they too can commit the crime above all crimes and never be held to account. Political expediency should never be allowed to take precedence over the rule of law and the upholding of justice.”

Lord Darzi of Denham

Lord Darzi of Denham

“I was born in Iraq to parents made refugees by the 1915 genocide… I say I’m a genocide survivor, and in thirty-three countries around the world, that description would be acknowledged. Yet, the country in which I have made my home, is not one of them. My great-grandfather, who lived in Erzurum, in what is now north-eastern Turkey, was executed along with his sons by the Ottoman forces. My grandmother, then just a teenager, escaped with her mother, and the two of them walked barefoot for weeks before finally finding sanctuary in Mosul, northern Iraq. They were the lucky ones – many other women and children were sent on a death march across the desert from which they would never return… “

Tim Loughton MP (Con – East Worthing and Shoreham)

Tim Loughton MP (Con – East Worthing and Shoreham)

“The Armenian Genocide remains one of the longest standing injustices in European history. The perpetrators remain in denial and too many bystanders have allowed the facts to be swept under the carpet and to turn the other way. With the recent international outrage at genocidal practices going on in the 21st century, not least through the appalling human rights abuses inflicted on the Uyghurs by the Chinese regime, it is imperative that we ensure that the world properly acknowledges genocides of the past to strengthen everyone’s resolve to call them out and prevent them being repeated in the future.”

John Spellar MP (Lab – Warley)

John Spellar MP (Lab – Warley)

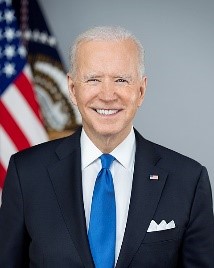

“US President Joe Biden and the US Congress did the right thing by recognising the Armenian Genocide. It is time the British Government did the same. Over 100 years have passed but still our government – and indeed the world – have not given the proper recognition that these atrocities deserve. Now is a chance to amend that wrong.”

Geoffrey Robertson AO, KC

“The treatment of the Armenian people by the Ottoman government in 1915 amounted to genocide. The present government of Turkey bears state responsibility for that crime as a matter of morality, and there may be ways of holding it liable in law… the responsibility of the present Turkish government is a responsibility engaged both by the international law rules of state succession and by the fact that the nationalist government that succeeded the Ottomans contained many of the politicians who had approved the genocide. Most significant, of course, has been Turkey’s obsessive denial of the truth of the genocide, a political stratagem of its successive governments ever since the issue was revived by the human rights movement of the 1960’s. This has taken the form of a massively funded international propaganda campaign, especially in the US, attempting to justify genocide…”

His Holiness, Pope Francis

A Message to the Armenian People on 100th Anniversary of Armenian Genocide, Vatican City, 12 April 2015:

“As Saint John Paul II said to you, “Your history of suffering and martyrdom is a precious pearl, of which the universal Church is proud …This faith also accompanied and sustained your people during the tragic experience one hundred years ago “in what is generally referred to as the first genocide of the twentieth century” [Pope John Paul II and the Head of the Armenian Church Karekin II, Common Declaration, Etchmiadzin, 27 September 2001]...It is the responsibility not only of the Armenian people and the universal Church to recall all that has taken place, but of the entire human family, so that the warnings from this tragedy will protect us from falling into a similar horror, which offends against God and human dignity. Today too, in fact, these conflicts at times degenerate into unjustifiable violence, stirred up by exploiting ethnic and religious differences. All who are Heads of State and of International Organizations are called to oppose such crimes with a firm sense of duty, without ceding to ambiguity or compromise.”

US President Joe Biden

US President Joe Biden

A Statement on Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, Washington DC, 24 April 2021:

“We remember the lives of all those who died in the Ottoman-era Armenian genocide and recommit ourselves to preventing such an atrocity from ever again occurring … We honor their story. We see that pain. We affirm the history. We do this not to cast blame but to ensure that what happened is never repeated.”

Conclusion

The UK is one of the few leading European countries that does not recognise the Armenian Genocide, contradicting not only the scholarly work of serious historians, including British ones, but evidence that can be found in its own archives. It is for this reason that the His Majesty’s government must pass a bill formally recognising the Armenian Genocide. It has a moral obligation to recognise this heinous crime and, following in the footsteps of many of its closest allies and with the benefit of the documentary evidence it holds, reaffirm its position in the world as a bastion of human rights, and against injustice.

Additional Media